As part of this year’s experiments, here’s one we did at Mansion Home.

A long-term concern of mine has been the old building infrastructure of northern Europe. Our buildings are not made for cooling in summer. I’ve had a few ideas over the years, but had a chance this year to try one out, thermochromic paint. We could paint rooftops white, but that then leads to loss of heat when needed in winter. Why not have paint with a high albedo when hot and a low albedo when cool?

With the support of Caroline Jack, our Private Secretary (she who must be obeyed at Mansion House), Russell Pridgeon of CDSM, and David Lamb, from our internal Mansion House team, we put three panels on the roof of Mansion House:

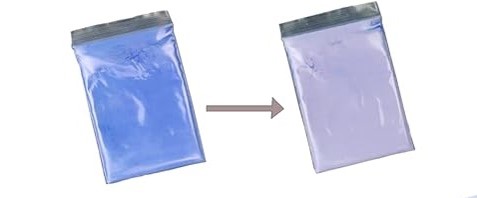

As you can see, quite an austere looking experiment. The team decided to re-use the abundance of existing materials at Mansion House, rather than ship even more in to become future archaeological relics. One white panel for high albedo, one black panel for low albedo, and the thermochromic panel changing in the middle. Behind each panel is a temperature logger taking a reading every 15 minutes over a period of months. The paints were purchased from the Little Greene paint company and the pigment powder was from SFXC, “Black 29°C”.

The panels are west-facing as this suited the available space, but also collects and reflects at the time of most importance for temperatures in Mansion House, late afternoon and early evening. This period is typically when we have high building occupancy and high heat during dinners and functions. Given the many gentlemen wearing ties and ladies wearing gowns, we don’t want our formal events to be uncomfortably warm.

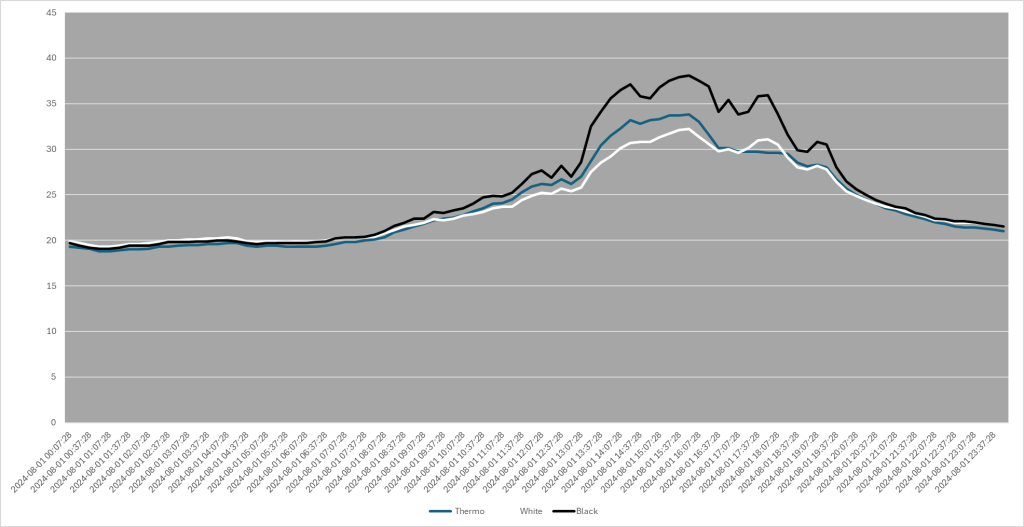

The team collected the data from the loggers at the end of September. On the chart below we see the temperatures measured on the back of each of the black (black) and white (white) control panels, and the thermochromic (blue) panel over the course of one August day. Interestingly the thermochromic panel can be observed to initially follow the temperature of the black roof, and then cool to follow the white roof as the colour changes:

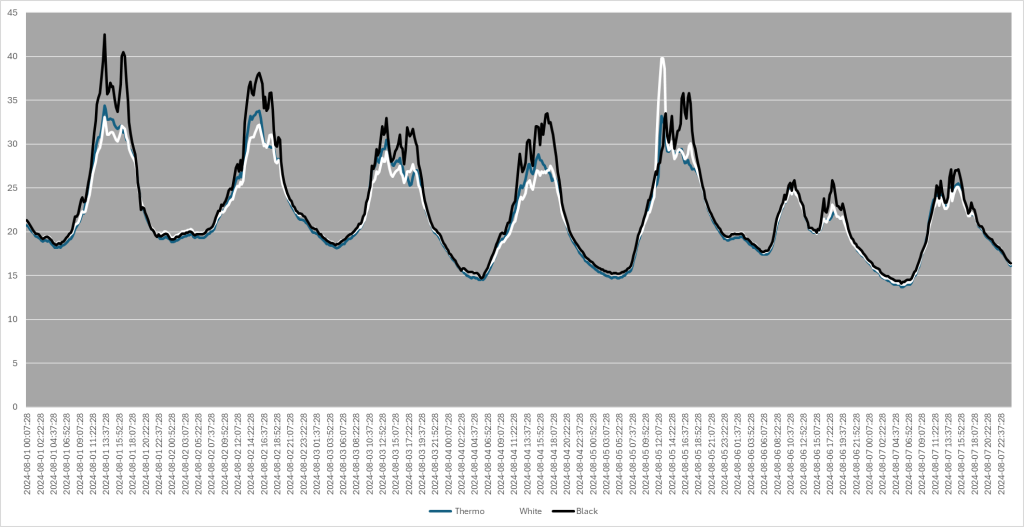

The chart below shows the thermochromic effect over several days:

Here you can see the effects of being exposed on the roof for around 6 weeks. This panel uses Dave’s “transparent waterproof glue” as the base for the pigment. It was hard to mix perfectly, and ideally we would get a paint R&D lab to suspend the pigment in the same solution they use for masonry paint.

Initially some poor instructions led to the team mixing the pigment in with the dark paint below, but we put that panel out as well, and surprisingly it still worked rather well.

From our limited work so far, it is clear that the pigment has a definite effect in limiting solar gain through our “roof”, and that when suspended in the glue it has proved far more resilient than we had feared.

Our first big unknown is a more exact profile of solar radiation to colour change point, which requires some lab work and/or simulation. As an initial experiment, we agree that the results fall into the “needs more looking into” category, obviously in a more controlled environment.

Our second unknown is activation and durability with exposure to London’s unpredictable mix of winter weather and ‘tropical’ sunshine. Everything is still running on the roof as we are keen to see how well the paint lasts in the winter rains.

As for our next experimental adventure on cooling? Convective air flow adjustment using dynamic cladding!