Remarks to: The 39th Cambridge International Symposium On Economic Crime, by Alderman Professor Michael Mainelli, Monday, 5 September 2022, at Jesus College, Cambridge

“Could A Little Bit Of Corruption Be A Good Thing”

A City friend of mine, Malcolm Cooper, tells the story of being in Washington DC with an African taxi driver. Malcolm asked the taxi driver how he found the USA compared to Africa and the response was, “What I like about this country is that it has a nice level of corruption.” It’s a more profound statement than you might think. The statement implies that corruption is universal but, as with Goldilocks and porridge, sometimes you can have too much corruption, and perhaps sometimes too little. So, while many economists talk about the distribution of goods, today I’d like to make a quick point about the distribution of bads.

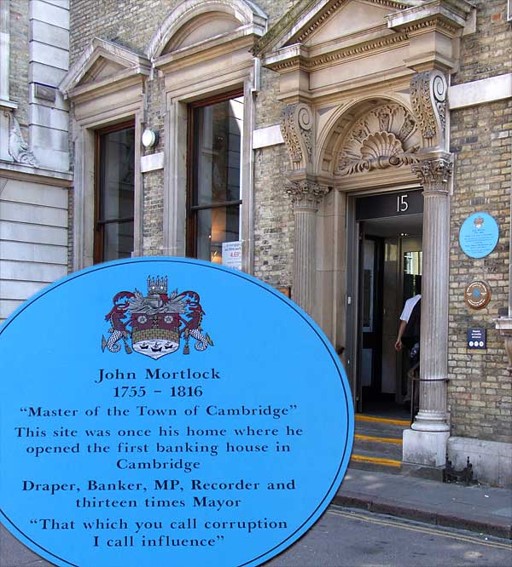

Corruption is: “the misuse of entrusted power for private gain”. There are taxonomies of corruption: bribery, graft, extortion, patronage, nepotism, cronyism, embezzlement, and kickbacks. Over the decades, I’ve always wanted to mention John Mortlock at this symposium. John Mortlock established the first bank in Cambridge in 1780. In 1783 he became an Alderman and changed the rules so that he held the post of Mayor of Cambridge 13 times until his death. Along with being Receiver of the Land Tax for Cambridgeshire and an MP, his offices allowed him to sell off city property at knock-down prices, divert taxes, and appropriate city funds. After his death, his sons continued the traditions. Mortlocks were Mayors of Cambridge for an unbroken streak of 51 years. This expert on the subject provided one of the quickest ways to dismiss allegations of corruption – “What you call corruption, I call influence”.

Global corruption is big, influential, and even economically important. Widely cited World Economic Forum numbers estimate corruption at about 5% of global GDP. The Copenhagen Consensus rated gains from reducing corruption as more beneficial for the global poor than improving infant and child nutrition, or preventing climate change.

Our firm, Z/Yen, investigates systemic corruption, from procurement to gambling and financial markets to media revenue protection. My first observation is that bureaucracy itself is intimately entwined with corruption.

Take anti-money laundering bureaucracy. If I were a criminal and all that stood between me and depositing or withdrawing lots of my money was convincing a bank teller that my identification was valid, I’d follow a young underpaid teller to the pub at lunch. There I would explain my predicament. Then I would return to the bank after lunch, slide a dodgy passport across the counter with £1,000 in it, have it photocopied at low quality and obtain my access. More corruption, not less. On the other hand, endemic government corruption in Albania plummeted quite a bit when their new government app went live during covid, thus eliminating bureaucratic corruption opportunities at government counters.

My second observation is that bureaucracy can impede solving systemic corruption. Like most systems, bureaucracies perpetuate themselves. For example, earlier this year Z/Yen conducted a study aimed at solving online fraud. At points, the biggest obstacles to reform seem to be the existing anti-fraud bureaucracies.

My third observation is the most contentious. Maybe we need corruption. Corruption is everywhere, just varying in degrees of severity. People talk about causes of corruption, but they’re really talking about environmentally favourable conditions such as a low level of societal trust, weak judiciary, weak rule of law, poor accountability, over-regulation, excessive bureaucracy, barriers to entry, underpaid civil servants, exclusive guilds, or elitist social structures.

Yet three things stand out. First, the strength of property rights seems to be a clear theme. North and Thomas note that “economic growth will occur if property rights make it worthwhile to undertake socially productive activity”. Corruption undermines property rights and thus impedes economic growth.

Second, inequality matters. At a 2007 dinner with Paul Volcker, he interestingly highlighted inequality as an important source of greed and corruption. With corporate US and UK executive remuneration frequently hitting $300,000 per day he questioned how executives can ever work. They have a full time job just spending their money. Many analysts note that countries with high equality, such as the Nordic countries, have low rates of corruption. They also have higher average living standards. Inequality leads to loss of trust which leads to corruption.

Third, trust is elusive. I frequently say that financial markets are based on mistrust. If I trusted people to pay for me in adversity, I wouldn’t need insurance, and so on. Uslaner points out that: “Corruption, of course, depends upon trust – or honor among thieves. As it takes two to tango, it takes at least two to bribe. Corrupt officials need to be sure that their ‘partners’ will deliver on their promises. In short, “I can trust you to cheat.” Until 2007 UK gambling contracts were unenforceable. This led to tremendous amounts of trust, at least about payment, in the UK gambling world. The law firm Dickinson Dees once advertised, troublingly, “If it’s legal – we’ll do it!”, implying that the ethical framework is identical to the legal system. Persaud and Plender disagree, “The nub of it is that much of finance is about promises whose fulfilment takes place over time. Those promises need to be sustained by trust, which cannot exist without an ethical framework.”[1]

Societal systems are messy, and some of that messiness makes us more vulnerable to corruption and fraud in the interstices. Yet, if societal systems were faultless, they might become unable to evolve when faced with novel problems. ‘Peccadilloes that pay’ do motivate some people to alter or bend the system. These people are rational agents breaking down information asymmetries and getting other people to reveal preferences that lead to resource reallocation, albeit also to theft and other illegal acts. Perhaps there is a grey area between corruption and faultless sterility.

Those who think corruption is endemic can look to other endemic risks for solutions. For example, alongside regulation, litigation, and prosecution, insurance has played a major role in the past in helping to manage risk. Recall that: development of fire insurance led to much better assessment and high standards leading to enormously reduced fire incidents; universal automotive coverage led to many fewer accidents and automotive thefts; workers’ compensation cover led to many fewer injuries; and non-compulsory home and contents insurance led to many fewer burglaries. If the only acceptable goal had been to eliminate fire or accidents, these solutions would have been ignored.

The current UK inflation target is 2% based on the Consumer Prices Index (CPI), not zero. Our fraud targets could be set similarly. Very low, but not zero.

In conclusion, some low-level corruption may serve a

purpose of helping to inoculate our systems and make them more resilient. Recognising that fact is not inconsistent

with hoping for a better future. ‘Fraud

is good’ if it helps us to figure out what needs fixing, i.e., that we learn

from it and strengthen our defences. For

example, what can corruption and fraud teach us about how to gain trust very rapidly? I am not tolerant of corruption, far from it,

but during this week we should also seek to learn from corruption.

[1] Persaud, Avinash D and Plender, John, Ethics and Finance, Longtail Publishing Limited, 2007, page 18.