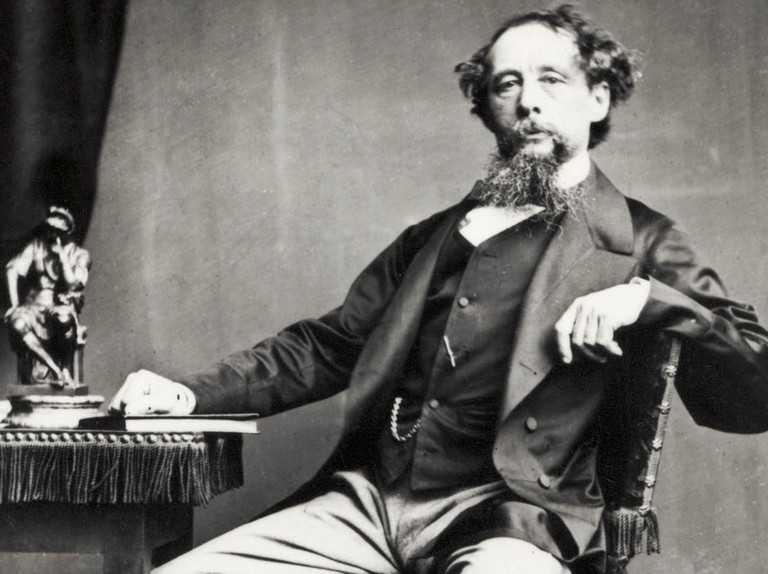

Toast To The Immortal Memory Of Charles Dickens (7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870)

Alderman Professor Michael Mainelli

Remarks to the City Pickwick Club at the George & Vulture, London, 25 March 2019

Mr Pickwick, Aldermen, Pickwickians, Distinguished Guests, it is my honour and challenge this evening to propose a toast to the memory of Charles Dickens. Thank you, Mr Pickwick, for your warm introduction. It is a delight to be able to address you here as, while I have lunched here since 1984, I have never had the pleasure of dining here.

Although there is a wealth of Dickensian material to mine, I suspect that this assembly of enthusiasts has mined it thoroughly. At first I read “Great Expectations”, but the inspiration wasn’t as good as I thought it would be. Dickens didn’t always think Americans worthy of mining his œuvre, scribbling in an 1845 letter to Lady Blessington, “I do not know the American gentleman, God forgive me for putting two such words together.”

2019 marks the quincentenary of Sir Thomas Gresham [say that five times swiftly] so I sought a Dickensian anniversary. A 200th left me trying to mine his seventh birthday, not likely to yield substance. A 150th takes us to 1869, just before the publication of The Mystery of Edwin Drood, and a year before his death. In fact, he sets out his will on 12 May 1869.

Suddenly, I remembered that Sailing Barge Alice Lloyd won the Thames Match of 1869, as you do. What’s the Dickens with the Thames Match? The Thames is a recurring stage throughout Dickens:

- David Copperfield, Gravesend and a cottage with an upturned barge that inspired Peggotty’s peculiar house.

- Great Expectations, Denton, the Ship & Lobster pub, as well as Gravesend Reach, Cliffe Battery, Blythe Sands, Allhallows and Cooling Marshes.

- The Uncommercial Traveller, The Lower Hope, canal and lime kilns, and the Isle of Grain.

Our Mutual Friend opens with, “In these times of ours, though concerning the exact year there is no need to be precise, a boat of dirty and disreputable appearance, with two figures in it, floated on the Thames, between Southwark bridge which is of iron, and London Bridge which is of stone, as an autumn evening was closing in.”

Tonight, the Thames shall connect 19th century lorries with rubbish, racing, and Our Mutual Friend.

19th century lorries. For 200 years the distinctive red ochre sails of Thames sailing barges sat atop boats of 80 to 95 feet. As late as 1903 a Joint Select Committee of Lords and Commons estimated that 75% to 80% of the whole traffic of London was carried by barges. Estimates of the number of Thames sailing barges trading at their height are about 10,000, but the barges “dug their own graves” by carrying the materials which built the roads for the lorries that replaced them. Today, there are about 30 sailing.

The English began modifying Dutch spritsail designs in the 17th century, visible in the Mansion House Harold Samuel Collection. The spritsail symbol still appears everywhere, in Nelson’s funeral engravings or Southbank University’s logo or the East London Bus Group logo. The sprit, combined with some early winches, gave the sailing barges an ability to carry 200 tonnes of cargo with two crew (“a man, a boy and a dog”). Logistics was crucial. Compared with, say, 200 horse carts and drivers, a barge’s advantages are clear. With trade on the tidal Thames, where tides can guarantee delivery less than 48 hours from Suffolk, Kent, or Essex, this is serious logistics.

I once had a dream I was being chased by one of these barges. It was a logistical nightmare. In reality, I was seduced by barges, buying the 76 registered tonnage sailing barge Lady Daphne and restoring her over two decades with Elisabeth.

Rubbish. As London’s population increased, the amount of rubbish soared. The principal character in Our Mutual Friend is Nicodemus Boffin, a dustman of “overlapping rhinoceros build”, “with bright, eager, childishly-inquiring, grey eyes”, who inherits £100,000. Boffin becomes known as the “Golden Dustman”.

Henry Dodd was the inspiration for the “Golden Dustman”, a contractor of City Wharf, New North Road, Hoxton, and good acquaintance of Dickens. Born in 1801, he started his working life as a ploughboy in the fields within sight of St Paul’s. By 1836 he had become a very successful ‘scavenger’, a refuse collector. Dodd seized this rubbish business opportunity by purchasing a fleet of sailing barges. The rubbish also fired brickworks he owned. He became very wealthy.

The Eddie Stobart of 19th century barges. A true “riches from rags” story. He also became a member of the Metropolitan Board of Works and was a Freeman of the Butchers’ Company.

Although Dickens describes Boffin as “A very odd-looking old fellow altogether”, there is no firm evidence that Boffin was the inspiration for the term – a quirky or peculiarly intelligent chap who gets you out of a pinch, like Q in the Bond films. Rather intriguingly William Morris, in his 1891 News from Nowhere, has his own Mr Boffin, described as a ‘dustman’ interested in mathematics.

Racing? Barge owners and barge skippers were at odds. They wouldn’t touch each other with bargepoles. Skippers might have mistresses from Ipswich to London. Tide tables were still a mystery and skippers would explain that these bulky flat-bottomed vessels couldn’t shift. Skippers hid their dalliances from ignorant landlubber owners, invoking weather and waves as reasons for delays. Dodd had a cunning plan to reveal all.

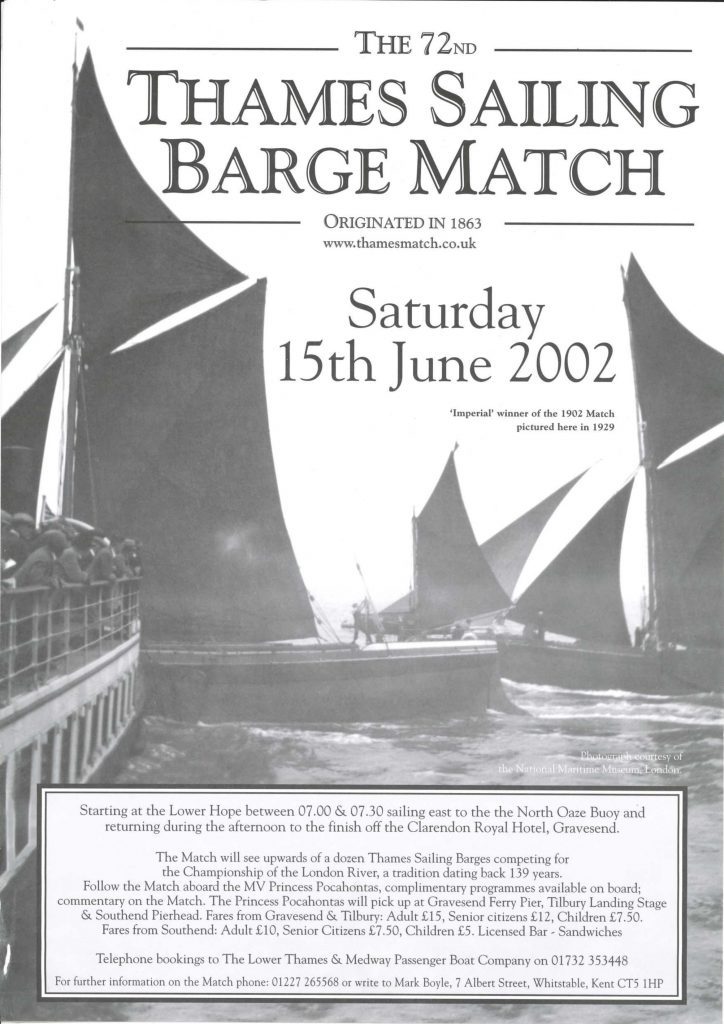

In 1863, with the support of the Prince of Wales Yacht Club, Henry Dodd proposed the Thames Match, a 48 mile course from Erith to the Nore and back. Many in society assumed that the event had Royal patronage, something Dodd did little to discourage, but in fact the yacht club was named after an Erith pub, the “Prince of Wales”. If alive today, Dodd would probably have a ferry contract with Chris Grayling.

Dodd wished to show, in his own words, “the value of the races, not only as sporting events, but as a means of advertising their usefulness as a means of transport and bringing to the public eye a better picture of what a sailing barge can do in the way of speed”. Think lorries at Silverstone.

Yet the winners came in under six hours, averaging over 8 knots. I imagine the smiling winner collecting his 10 guineas and then realising that his boss, Dodd, was smiling too, with proof of how fast these barges could really move. Who had really won the match?

From the start the matches attracted many dozens of barges, and over 10,000 people took passenger steamers for day trips from London to watch. In the latter years of the 19th century, the event was even covered by Dickens’ son in his annual gazetteer.

By the time of his death in 1881, aged 80, Dodd was worth over £100,000, of which he gave £5,000 to the Fishmongers to keep the Thames Match going. That’s £500,000 to £2.25M in today’s money, depending on which index you favour. It amounts to £500 annually. This year’s Match is on 22 June.

Our Mutual Friend came in 19 instalments starting in 1864, but the 1865 Staplehurst train disaster had an enormous effect. The only first-class carriage to remain on the track was Dickens’. Before rescuers arrived, Dickens tended and comforted the wounded and dying with a flask of brandy and a hat refreshed with water.

Fortunately, Our Serialising Friend remembered to go back to the train wreck to retrieve the manuscript for the 16th instalment. He recorded his thoughts on the disaster in the book’s Postscript. His son said he never recovered from the trauma, dying five years later to the day.

Today, Our Mutual Friend is mostly remembered as promoting Great Ormond Street Hospital. Dickens has the orphan boy Johnny Higden brought to “the Children’s Hospital” terminally ill with tuberculosis.

On re-reading Our Mutual Friend for this talk, I was struck at the ‘organic’ view of London, a living creature constantly recycling its waste and its people, all down the Cloaca Maxima of the Thames. Not for nothing did Dickens focus on the “where there’s muck there’s brass” character of Dodd. He also knew “where there’s muck there’s humour”.

Terry Pratchett emulated Dickens in his Discworld novels with the urine merchant Harry King. “H. King – taking the piss since 1961” who on the insistence of his wife changes his slogan to “recycling nature’s bounty”. As well as an impressive fleet of honey-wagons, Sir Harry runs a fleet of river barges. His personal barge is the Lady Euphemia. Like Stobart, and Mainelli, Harry’s vehicles have ladies names. That said, Harry King incorporates Guy Ritchie anti-heroes in Jimmy Hoffa plots.

The great thing about Dickens is his accessibility. We can see the good old days through the lens of London and realise that the best thing about the good old days is that they were neither wholly good nor old, but eternal.

In Nicholas Nickleby, Dickens writes, “Bring in the bottled lightning, a clean tumbler, and a corkscrew.” I say, please raise your glasses, stand, and join me in a toast to “The Immortal Memory Of Charles Dickens”!

Online References

https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.95808/2015.95808.The-Dickens-Companion_djvu.txt

https://omf.ucsc.edu/scholarship/bibliography/chesterton-text.html