Caledonian Club, London, 11 February 2005

Your Excellencies, Distinguished Guests, Lords and Ladies, Highlanders and Rabbie-like Lowlanders, Waiters and Waitresses, … and uhm, ahh yes, native English people.

It is my great pleasure to thank each and every one of you for joining us in this celebration of Scotland’s Bar d. To me falls the dicey situation of proposing the toast to the host country, England.

d. To me falls the dicey situation of proposing the toast to the host country, England.

Although in Scottish terms I’m genetically poor, in Scottish experience I’m rich. Since I notice that no Scots have risen to the occasion, this must be a particularly tricky slot.

When David Ainsley asked if I’d be prepared to give this address, I wondered what qualifications I had other than a voice and a pulse. I was told that we would have some of the best English in the country here tonight. That’s great, because none of the best English in London were bothered to come. There have been so many speeches this evening that surely I am 16th or so, but 16 is my lucky number, which I remember well from my glorious rugby days!

As I prepared for this evening, I began to realize that I am truly a bit of an amateur anthropologist – I love the native peoples, their quaint customs, their curious habits, their strange speeches and mannerisms, their bizarre marriage rituals – and that’s just Chief Lady Windsor’s tribe.

Born in the USA, the son of an American-Italian father and an American-Irish mother who started school in Italy and then moved to America where I acquired that most perfect English accent – I began work in Switzerland and find myself today with a French son and German daughters – yet I feel rather qualified to give this toast as, not only have I had first hand experience of indigenous peoples around the world, I have also lived in England for a quarter of a century.

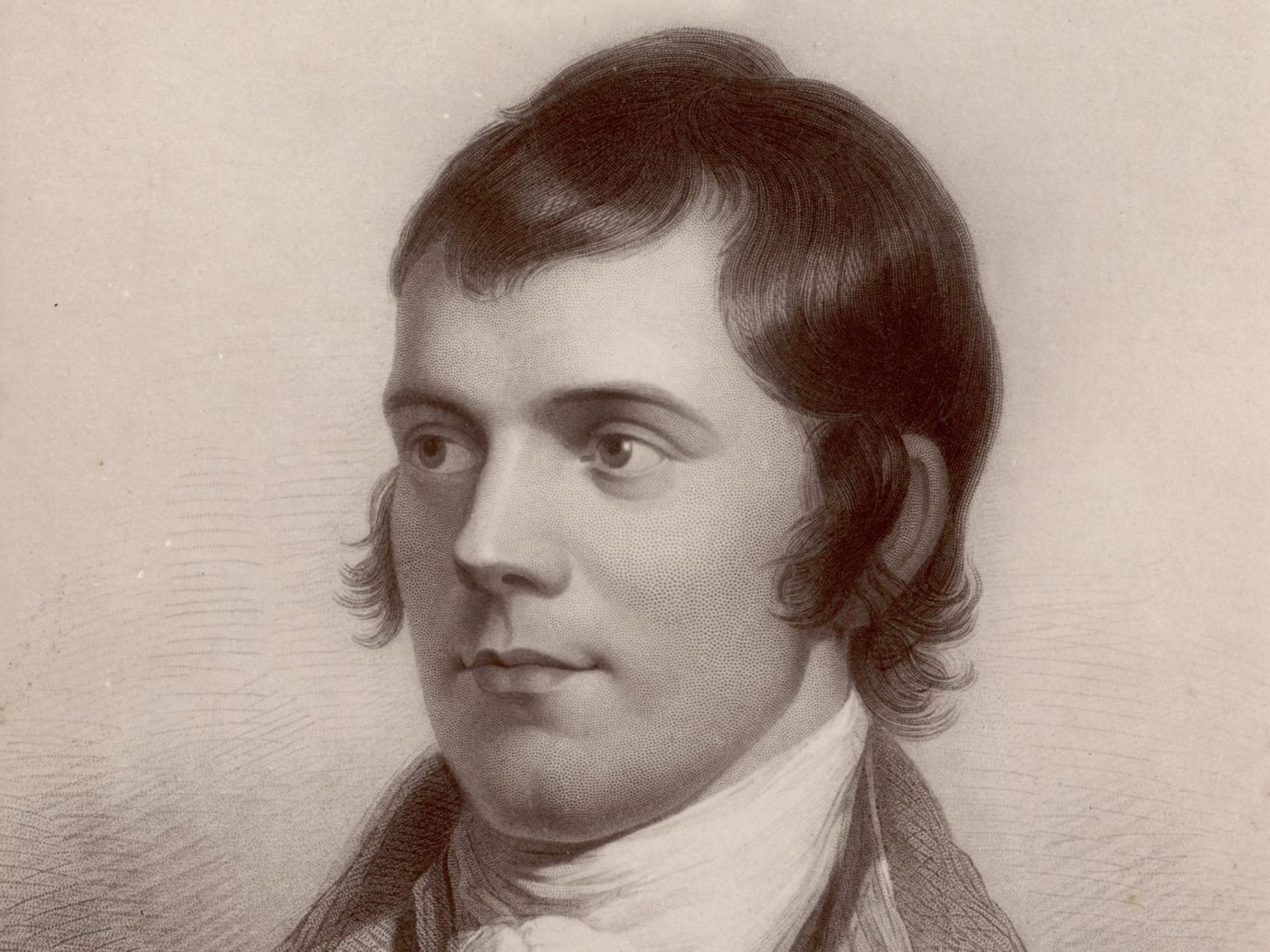

As a Scottish Highland Bagpiper, yes verily, although that famous English native and Scottish tour book author, Samuel Johnson, might quip that “he may not do it well, but you’re surprised to find it done at all.” I have had the privilege of attending Burns’ Suppers for over 30 years. I have always enjoyed the rich ceremony and ritual – watching the Haggis being piped to the table, hearing the blood-curdling Address, seeing the relief on people’s faces when the real food is served.

Which reminds me of a story that the great gag writer Barry Cryer tells about that fantastic, native comedian Tommy Cooper. When Tommy Cooper was on military service with the Horse Guards he was assigned palace sentry duty but fell asleep standing inside his sentry box. While in the middle of this court martial-able offence, he half opened one eye to see that his Commanding Officer and the Regimental Sergeant Major were fast approaching to discipline him. Closing his eye again he sought a single, killing word that might free him from this predicament. He shook himself, drew to his full height, opened both eyes and then said the one killer word that could save him – “AMEN.”

So let us find that one killing word for the English.

At a solemn occasion such as this, our thoughts turn to better things, better things abroad. Aye, there’s a word to start with, Abroad.

Many of us here have left our county of birth, exchanging our familiar family, friends, language & culture to settle in a foreign land – for many rich and varied reasons, not least in the case of David Ainsley. Even Rabbie Burns himself contemplated emigration in 1786 to seek his fortune, penniless after an attempt at a Private Financial Initiative at flax growing and heart-broken over Mary Campbell:

For lack o’thee I leave this much lov’d shore,

Never, perhaps, to greet old Scotland more.

However, not even Rabbie contemplated emigration to England, so he booked passage on a ship from Leith bound for Jamaica. Yet, as we well know, and much to the relief of later generations of Scots, Caledon-ophiles and Haggis-lovers the world over, he chose to stay.

We have heard some of Burns’ rousing and best-known works already tonight. Somewhat less familiar to you may be a song, which he wrote about the daughter of William Stewart, factor of the Closeburn estate. As an Excise officer, Burns frequently visited Stewart while on Customs business, and even wrote him a song “You’re Welcome, Willie Stewart”. Burns’ attention inevitably turned to Willie’s daughter, Polly. Now, Polly led an erratic life. She married her cousin, by whom she had three sons, then lived with the farmer George Welsh and finally formed another association with a Swiss soldier called Fleitz, with whom she went abroad – there might be a theme here. Burns recycled her Dad’s poem as the song Lovely Polly Stewart. Here is the chorus:

O lovely Polly Stewart,

O charming Polly Stewart,

There’s ne’er a flower that blooms in May,

That’s half so fair as thou art!

In a flight of fancy, I wonder how this song might have come to be written, if Burns, heart-broken, had taken ship in 1786, bound for Jamaica. Taking the recently privatised SouthWest Tallship Lines, owned by a special purpose vehicle recently placed in administration, he would have been promptly compensated under the Steerage Ombudsman and Indenture Unitary Charge scheme.

He would have passed by the “off balance” sheet land of England and upon following his “cool runnings” arrived in Kingston a scant seven years later. Had this happened, Burns would have changed the entire course of reggae. Being a literary man, and already familiar with another throat-challenging language, Burns-the-dude’s works would have been re-imported in the 1970’s to my first English home, Brixton, and sung by the likes of Bob Marley, perhaps something like this:

O licky-licky Polly Stewart

O jammin’ Polly Stewart

Der be no bloss dat show in May

Dat haf so ketchy-chuby art.

But history did not happen that way – Rabbie Burns did not choose to emigrate to either Jamaica or England. He stayed at Edinburgh to become an Excise man, a farmer and Scotland’s national poet and vagabond. Sadly, we wind up back on these shores – the word Abroad does not fit.

But what has happened in England from 1786? Did the natives that Burns was too terrified to live among develop further, did they progress, what of their running water, did they gain the power of speech?

So what one word would I use to describe the English?

Perhaps the word is spiritual (Stonehenge, Winchester Cathedral), but then I remember why God gave such a non-religious people as the English cricket – so they could develop a sense of eternity.

Perhaps the word is trustworthy. But then I remember that the sun never set on Perfidious Albion’s empire because God doesn’t trust the English in the dark.

Is it that Greek word, oxymoronic? Possibly, as there are so many English oxymorons:

- English plumbing

- English engineering

- English punctuality

- English sexuality

Perhaps the word is generous? The English have given so much to so many.

- their national cuisine – well that’s been given to the Indians, the curry

- their government – well they’ve long since given that to the Scots

- as holders of one of the few remaining European currencies – nevertheless they also gave that to the Scots

- their colonies – thanks, but we won them fair and square

No, I think that the one word I would use is tolerant. The English are a tolerant people – and for that we love them. They are tolerant to all foreigners, having us in their land, allowing us to make fun of them and to share their sense of humour and fair play.

On such a literary evening, I would like to end with a small paraphrase of that great English poet, Billie, Billie Shakespeare.

Friends, foreigners, lend me your ears;

We come to praise the English, not to marry them.

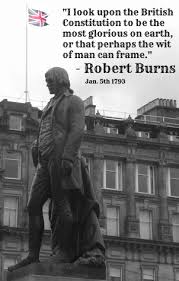

The noble Burns hath told you the English were strange:

But the English are a tolerant folk;

So are they all, all tolerable men.

So during this dinner, the English have moved from being just an anthropological curiosity, the quaint and cute local natives, to one of this Earth’s most tolerant people. Not bad for one evening.

Or as that famous North African comedian, Tommy Cooper, might say, a sincere “AMEN”.

Honoured companions in a foreign land, it gives me great pleasure to ask you to be upstanding and drink a toast to our hosts – the English.